Haiti Gives New Recognition to Vodou

Kathie Klarreich,

Christian Science Monitor

For many in the West and in upper Haitian society, Vodou--also spelled Voodoo, Vodoun, and Voudou--evokes a Hollywood stereotype of black magic and dolls stuck with pins.

But for Vodou supporters, what was once an underground practice dating back to slave days is finally being acknowledged as a bona fide religion and recognized for its role in defining Haitian culture. Vodou, which has no written scriptural text, is an amalgam of beliefs taken from African, native, and the colonial cultures that shaped modern Haiti.

The Roman Catholic and Protestant churches in Haiti have a long history of trying to discourage Vodou, seeing aspects of the faith as incompatible with their basic tenets. These include the worship of many spiritual beings, or lwa; a belief in possession; the use spells and incantations for good and, in some cases, for evil; and the use of animal sacrifices for some ceremonies.

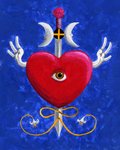

Culture minister Jean Robert Vaval is among those working to improve Vodou's image. He recently helped arrange an exhibit of sequined Vodou banners and mock altars at the Musee d'Art Haitien in the capital, Port-au-Prince.

"We have maintained our heritage through Vodou," Mr. Vaval said. "We were brought over here from Africa, from tribes that no longer exist. We got all mixed up into one people. From that point on we created, and a great source of our inspiration has been Vodou."

The Culture Ministry's float for this year's Carnival paid homage to a 1794 Vodou ceremony that led to the country's independence from France 10 years later in a rebellion led by a former slave.

For practitioners, or Vodouisans, Vodou rituals are part of a philosophy that ties individuals to society, their community, and the environment.

Although there are no official statistics, the conventional wisdom is that the country is 80 percent Roman Catholic, 15 percent Protestant--and 100 percent Vodou.

"Vodou provides, like all world religions, a profound spirituality," says Leslie Desmangles, professor of religion at Trinity College in Hartford, Conn. "It is a very strong, cohesive social force within the community, and the community extends beyond the visual community to include the spiritual world."

In a country overwhelmed by poverty, political instability, and poor health care, oungans and mambos--Vodou priests and priestesses--are consulted on everything from fertility to serious illness to property disputes and even politics.

"There has never been a Haitian president who hasn't used Vodou to promote his program on the Haitian people," says Desmangles. "Every president has used it to maintain power through theological language."

Former dictator Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier, president from 1957 until his death in 1971, was notorious for his use of Vodou. Loyal clergy reputedly performed rituals to protect his personal paramilitary force, the Tonton Macoutes, from retribution as they terrorized the Haitian populace.

In contrast, former President Jean Bertrand Aristide was the first Haitian president to formally invite Vodou oungans and mambos to the National Palace during his 1991-95 administration, recognizing the role they play in shaping Haitian society.

"Vodou is a manifestation of our lives," says musician Wilfrid "Tido" Lavaud. "It is part of our culture and influences everything--from the way we talk, to how we eat, to the colors we use in our paintings and the rhythms we include in our songs."

Vodou is so entwined in Haiti's culture that it is practically impossible to separate the two, say supporters. Traditional Haitian dancers in bright costumes often are accompanied by drummers who pound out African-style rhythms to honor ancestors and specific spirits. Walking down the street, one sees veves--traditional designs meant to invoke a Vodou spirit--in buildings and windows.

In Haitian painting, green is often a tribute to Simbi, patron spirit of rain and drinking water, while pink is a reference to Erzulie, the patron of love.

"We are a people with a tremendous amount of imagination," says Pradel Henriquez, the Culture Ministry's director of artistic and literary creation. "Haitians are not profoundly happy, but they want to live their lives to the fullest."

Sanpwel is not a Vodou religious phenomenon,

Sanpwel is not a Vodou religious phenomenon,